The Size of Dolphin Dorsal Fins, Comparing Males and Females

- Jan Ostman-Lind

- Sep 1, 2025

- 6 min read

Why do the dorsal fin size differ between males and females in so many species in the dolphin family (Delphinidae), where adult males have larger dorsal fins than adult females? This is a question that has not been studied very much, since, in order to conduct such a study, you first need to be able to sex, or determine the gender of, individual dolphins in the wild - something The Smyg, our underwater viewing vessel, was designed to do (see this blog post). So if it is too hard to determine the gender of dolphins in the wild, we may be able to shed some light on the question if we can understand the purpose of a dorsal fin.

The dorsal fin has several functions. One of them is to serve as a vertical stabilizer, stabilizing the animal when it turns. This is why almost all fish have one. Sharks, just like dolphins have dorsal fins that stay upright at all times, while many bony fishes have dorsal fins they can put up when needed, for example when making a turn. This is crucial to all these predators when hunting for food, just as it may be crucial to the prey, when trying to get away. As an aside, the fact that all these aquatic animals, evolving independently hundreds of millions of years apart, all have a dorsal fin, is an indication that it is a crucial piece of anatomy for a fast-swimming lifestyle and a great example of convergent evolution.

There are a few examples of delphinids without a dorsal fin, like the right-whale dolphins. These are beautiful, spindle-shaped animals that roll over on their side when they make sharp turns. There are two species, the Northern and the Southern right-whale dolphin.

Most delphinids, however, do have a dorsal fin and they can make sharp turns while remaining upright. So, it would be interesting to find out how the right-whale dolphins lost theirs, if they even had one to begin with.

The dorsal fin, together with the pectoral fins and the tail flukes, also serve another important function for these active animals and that is to shed extra heat to the environment to cool down when they exert themselves. All delphinids have a more or less torpedo-shaped body. This is a great adaptation to life in the ocean, not only because it is hydrodynamic, offering less resistance when moving, but it also helps to maintain a mammalian body temperature in an environment that is much better at removing heat than air. This is because this shape, lacking appendages like long arms and legs, can hold a larger body volume relative to a smaller skin surface area (a lower surface-to-volume-ratio). Humans, by contrast, have a much less efficient shape in this respect, since our arms, legs and head increase the surface area relative to our total volume, giving us a much higher surface-to-volume ratio. In addition, the delphinids also have an insulating layer of blubber to further help keep the heat in. As a result, they have no problems staying warm in the ocean.

However, delphinids may have a problem when they become very active, such as when they chase prey or interact energetically with others. At this point, their highly-efficient shape makes it harder to lose all the extra heat their muscles generate. This is where their various fins come in - like the radiator in your car, they provide extra surface area through which these animals can release heat to the surrounding water, when needed. Their bodies can direct the blood in their fins based on whether they need to conserve heat (direct most of the blood in vessels deeper in their body) or lose heat (direct the blood to vessels close to the surface in their fins). We can also adjust our blood flow based on body temperature - our skin surfaces turning pink when we exercise or ‘lose color’ when we’re cold, due to the blood being directed away from the skin surface, to deeper in our body.

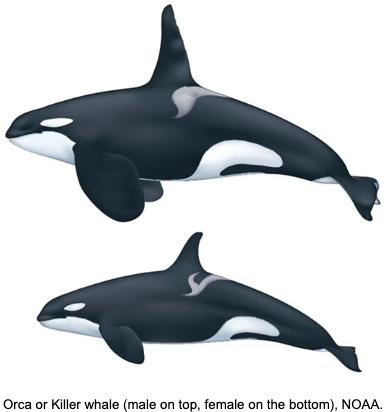

But why would male delphinids need larger dorsal fins than females? In some cases it may be explained by the size differences between males and females - if males grow to be bigger in general, you would also expect their dorsal fins to reflect this. This is one instance when you actually can sex the adult males, since they are bigger - smaller animals can either be an adult female or a subadult. A good example of this is the Orca, or killer whale, where the adult males are significantly larger than the females and, as a result, have much larger dorsal and pectoral fins and tail flukes.

There is a physiological explanation for larger fins in larger marine mammals, that has to do with surface-to-volume ratio (see previous blog: Why are Marine Mammals so Large). Since the males are larger, they will generate more heat, so they will need to be able to get rid of more extra heat than females. The amount of heat they generate depends on the number of cells in their body. This will increase by a factor related to the cube of the animal's length (length3). The amount of heat they can lose to the environment depends on their surface area. This will increase by a factor related to the square of their length (length2). So when an animal grows larger, the number of heat-generating cells will increase much faster (length3) than the surface area (length2) of its skin, through which it sheds excess heat. This discrepancy can be countered by increased fin size, explaining some of the difference in fin size (including the dorsal fin, pectoral fins and tail flukes) between male and female killer whales. These additional features increase the total surface area of the animal a lot more than they increase the animal's volume. However, it is not only the size of the dorsal fin that differs between the males and females - the males also have a different fin shape.

Also, there are several species of dolphins where male and female animals are about the same size, but where the males have both somewhat larger and differently shaped dorsal fins. One group of species where this is the case are the spinner dolphins. There are several subspecies, including the Hawaiian spinner dolphin that Kula Nai’a studied. An extreme example is the Eastern spinner, found in the Pacific ocean offshore of central America. This species was studied extensively, being killed by the thousands in the dolphin-tuna fishing industry in the 1960’s and 70’s. The male dorsal fins start to grow much faster in the trailing edge when they become subadults, reaching sexual maturity (like human teenagers). As a result, when they reach full adulthood, it looks like the dorsal fin is put on backwards.

The same thing appears to happen to subadult male Hawaiian spinner dolphins, although not as extreme. Of the 52 male and 16 female spinner dolphins that we were able to identify and sex, the dorsal fins of the adult males tended to be larger, more upright, and with a straighter trailing edge than those of adult females.

However, we were not able to determine the age of our study animals very accurately. We only had a few individuals identified from previous studies (see photos above) that we definitely knew were adults. One of the adult females had much of the top of her dorsal fin removed, making it hard to estimate what it would have looked like had it been intact (see photo below).

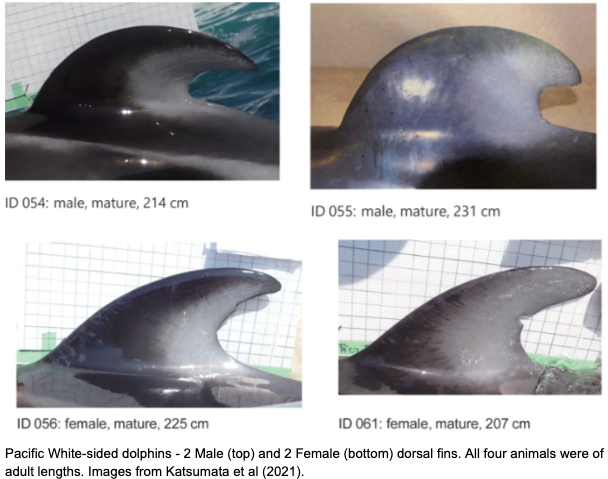

Another example is the Pacific white-sided dolphin, where male and female animals are about the same size, but where the males have larger dorsal fins, with a very different shape than the dorsal fins of the females

It could be that this is a marker allowing other dolphins to identify the individual as an adult male. It might also help adult males outmanoeuvre younger, competing males or same-size females. This is something that has not been studied very much.

I want to end this blog by mentioning a small species of toothed whale that is not very well known - the Spectacled Porpoise. In this species the size of the adult male dorsal fin is much larger than that of adult females, even though the size difference between male and female animals is minor. It seems to require some additional explanation and it would be fascinating to study the social interactions of this species, especially during the mating season.

This species is not well known, primarily because of where it lives - the Southern ocean. It has been seen around the tip of South America, Tasmania and some of the oceanic Islands, according to the Whale and Dolphin Society. It is found in smaller social groups (1-5).

Reference:

Katsumata, E., Naruse, S., Hosono, T. and Katsumata, H. (2021). Sexual Dimorphism In the Dorsal Fin of Pacific White-Sided Dolphins (Lagenorhynchus Obliquidens) from Coastal Waters off Japan. Cetacean Popul. Stud. (CPOPS), Short paper Vol. 3, 2021, 273–280.

Lipsky, J.D., and Brownell Jr., R.L. (2018) Right Whale Dolphins Lissodelphis borealis and L. peronii: Lissodelphis borealis and L. peronii. Encyclopedia of Marine Mammals (3d Ed.), pp. 813-817.

Comments